Sea-Eye

Description: Creating and editing pictures, videos and interviews on board of the rescue ship Alan Kurdi.

Company: Sea-Eye

Job title: Field Media Coordinator

Location: Central Mediterranean

Year: Mar 2020 – May 2020

Context

Sea-Eye is a Search & Rescue NGO in Central Mediterranean that prevented more than 15.000 deaths at sea since 2015.

I participated in the mission AK2002 as Field Media Coordinator (FMC) which turned out to be the longest mission the NGO had. It was also the first time we had 150 rescued people on board of the Alan Kurdi.

This “odyssey” happened during the pandemic between March and May 2020.

My role was to document the mission with pictures, videos and interviews. Through my work, I was the connection between the life on shore and the life on the ship. I worked tightly with Sea-Eye’s Press Office and journalists to provide all the necessary information.

Like every other crew members, I also had duties on board such as maintenance, spotting and deck watch.

The report “The torture factory” reminds us that 85% of the 3,000 interviewed people who had reached Italy from Libya had been subjected to “torture, violence, and inhumane and degrading treatment” in Libya.

Let’s embark on this journey together.

Short reminder: this article is part of my portfolio. It emphasizes my work as a Field Media Coordinator. It’s not made to be a detailed resume of the rescues.

What problem did I solve?

Departure from Spain

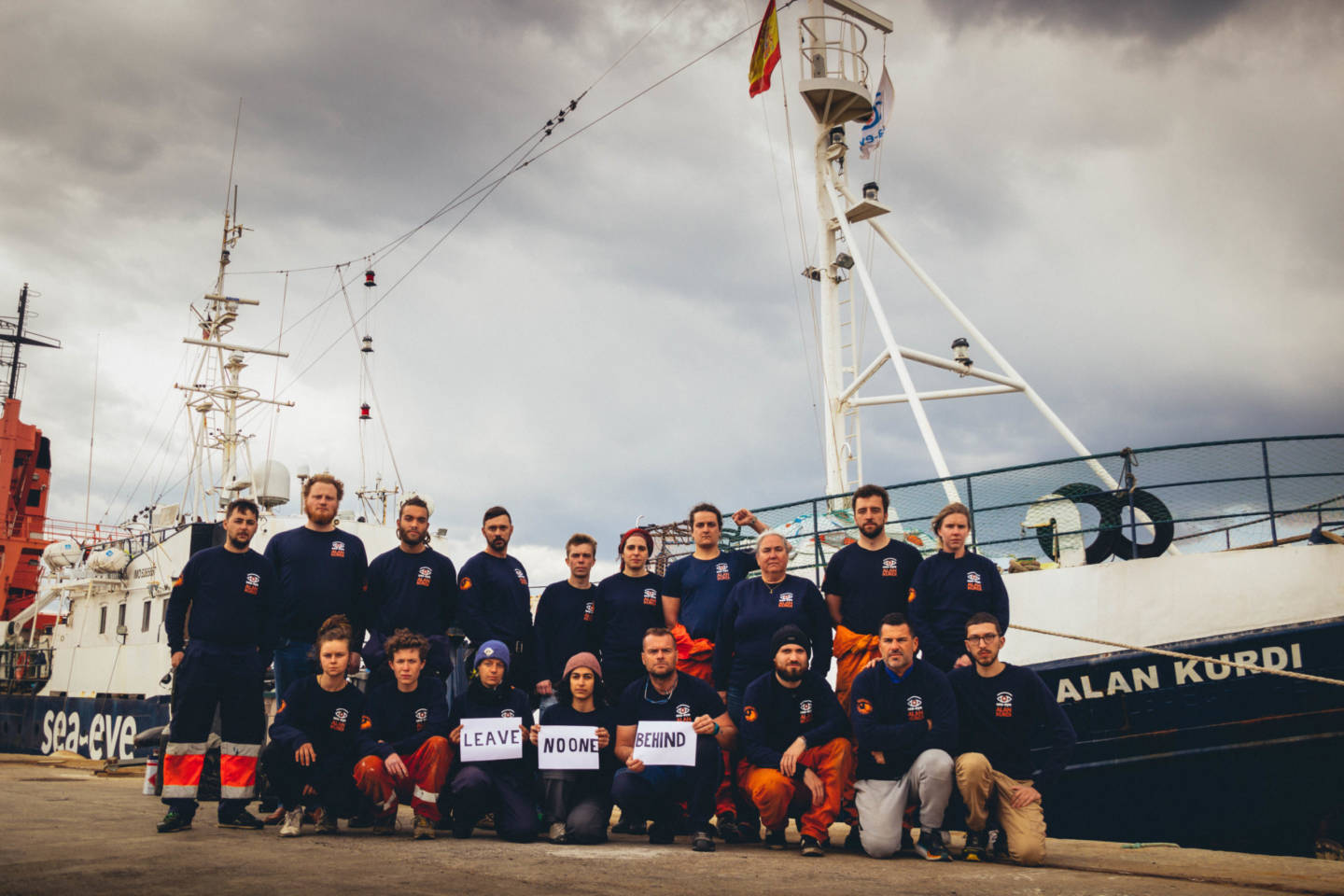

As soon as I arrived in Burriana, Spain, I had to be ready and share content on a daily basis. In a difficult and unique pandemic context, we couldn’t do “fun stories” by sharing “how is life on board”. Therefore, we kept a serious communication and took part on the growing #LeaveNoOneBehind that was getting a lot of traction in Germany and on the Greek islands.

After two weeks at the port, we were finally allowed to leave. For the public, our announcement on social media was a great surprise. Indeed, we were going to be the only rescue ship able to go and report about the situation on the SAR zones while the whole world was on lockdown.

Conduct interviews with the crew

I conducted the interviews when needed and accompanied the crew by giving tips and helping them to have a clear message. The crew was well aware about the importance of communication. They wanted to be sure their communication wouldn’t cause harm to anybody or be used against the NGO.

After every dinner, I was doing the “media minute” to keep the crew members connected with the outside world. I also used that time to talk about communication, ethics, white saviourism, and reply to all their questions to reassure them about media on board.

The two rescues

During the first rescue, a Libyan militia arrived and threatened the people who then jumped into the water. I became a Human Right Observer (HRO) where every content can become a legal evidence or an advocacy tool. With the great work from the rescuers, we had no casualties.

A second rescue happened few hours later next to oil rig platforms. At the end of the day, we had 150 people on board of the Alan Kurdi.

«The smuggler told us to follow the light, that it was Italy.»

It was an oil rig, 80km away from the Libyan coast. They didn’t have enough fuel to travel the remaining 400 km to reach Sicily.

On stand-by

As soon as we rescued the people, Malta made a declaration that they won’t accept us. Italy and even Libya closed their ports to foreign ships in the following hours.

On board, our work was to care about 150 people, maintain a calm atmosphere and cook food. Nobody had internet except the captain, the head of mission and I (FMC).

On shore, the headquarters (HQ) is working hard to find a port for us.

Therefore, my work is to communicate on both directions about what’s happening on the other side. We communicated to the media about our medical measures to face the pandemic and about the dire conditions people had on board.

We waited 11 days. During this period, we had two medical evacuations, two supply deliveries and one person who jumped overboard to try to reach the land. In the end everybody was safe.

We transferred the people to a Ferry in Palermo. We then had two weeks of quarantine before to leave back home. The ship Alan Kurdi was detained by the authorities for about two months.

How politicians used the pandemic to further delay rescue operations.

By being the only rescue ship on the SAR Zone during the pandemic, we took a strong stand on “Leaving no one behind”. It forced governments to withstand their obligations and welcome rescued people.

The authorities used well-known strategies to further delay our work. They did not respond to the emergency calls from the Alarmphone; they first denied us, then took eleven days to give us access to a safe port; they forced us to both quarantine & do a test; they conducted extended verifications on the ship; they used loopholes to detain our ship.

All these strategies were discussed during two webinars. One below with Transform! Europe, and one with the Centre for Advanced Migration Studies from the University of Copenhagen.

Read more:

The Guardian – ‘Migrants never disappeared’: the lone rescue ship braving a pandemic

La Croix – Méditerranée : un navire part à la rescousse des migrants

The Guardian: Italy declares its own ports unsafe to stop migrants disembarking

The New Humanitarian: How COVID-19 halted NGO migrant rescues in the Mediterranean

Sea-Eye: Odyssey of the Alan Kurdi rescue ship ends

How did I solve it?

Beside being an actor of this journey, I brought to the FMC’s position my own experience. Working two years on Lesvos, I had the opportunity to work a lot on creating content for social media and reflect on the deeper meaning of the impact of my work.

Being a FMC

When I arrived on the ship, I was surprised that guidelines for FMCs were only shared orally. We were rather given a large flexibility on creativity because HQ trusted the experience of every FMC they selected. It was an interesting stand but my experience made me say that some boundaries and written documentation had to be made because

- the lack of time and stressful context often brings a lack of vision. On such scenario, ethics tends to be easily forgotten;

- being in charge of such a diverse range of mediums (photography, film-making, interviews, …) can be difficult. It’s quite common that people are only specialized in one of them and need “quick tips and tutorials” to catch up the other mediums.

- it’s important to have a clear code conduct that we can refer to, for ourself or for the crew members. It’s important to teach the crew members about our role.

- explaining how might evolve a mission can help a lot the FMC to anticipate a momentum and be ready on time with the right equipment.

So, at the end of the mission, I submitted a 78 pages interactive document to better train next FMCs. The document called “handover & feedback for next FMCs” included sections such as pre-departure questions, timeline of a mission, responsibilities, training the crew members, release form, interaction with guests, posture as FMC, creating ethical content, human right observer’s role, and a quick access to selected in-depth tutorials for photographing, filming, interviewing people & editing content.

To give a few examples:

- A page about framing: how a high level shot conveys dominance over the subject while an eye level shot conveys a sense of equality. Framing is important to avoid “White saviourism” imagery.

- Quick access to tutorials about lighting and sound recording can help FMCs who are being challenged by the constraints of filming on a ship. It can help to reduce stress and increase efficiency on filming and editing.

- Introducing ethical guidelines and form release help FMCs to keep high standards. Especially when FMC will be facing difficult choices such as showing people in situation of vulnerability or people’s face. The guidelines are not restrictive, they are trying to bring awareness so the FMC can take conscious decisions depending on a given context. It’s also important for FMC’s mental health to not retroactively regret its choices.

Bringing feedback to improve next missions

Finally, I also brought my experience in conducting workshops and debriefs. I leaded the debrief of the rescue operations. And, at the end of the mission, we took two evenings to gather feedback, brainstorm and bring solutions to the HQ. We shared two proposals to the HQ to improve the next missions.

The extra mile

The drawing called “Mémoire partagée” (Shared Memory) brings awareness about what’s happening at the EU borders and specifically in the Central Mediterranean Sea. I started it during the mission. I gathered 400 words from the 150 guests and 17 crew members. The words are now lost within the myriad of black lines.

This artwork is like a timeless brain: scientists say that our brain can remember everything, information is just lost in our unconscious. And to re-access this information, you need associated thoughts or experience.

Here it’s the same, the artwork is a brain full of shared memories from people who flew a war-torn country and crossed a sea.

It becomes an exposed time capsule where the words will only pop-up to the eyes of people who experienced such a difficult journey. But maybe with a lot of efforts, you could find and read a few words?

It’s a 118.5cm x 83.5cm Admiralty map of Valletta harbours and lines drew with fine point marker.

The extra extra mile

Knowing my limited amount of time on board of the ship, I wanted to experiment as much as possible. Creating artworks was also a way as a FMC to communicate about this topic using different mediums that could later be exhibited.

This picture is part of a serie of solarigraphies that I made with the help of “Solarigraphy2010”. Solarigraphy is a simple handmade light-tight box (a soda can) with a pinhole in one end, and a photographic paper wedged on the other end. The process is a long exposure where light “activates” the paper and creates an image. It creates a unique picture where: moving elements are transparent; non-moving items stay sharp; and the sun leaves its complete path.

This picture is a journey. What can you see? The RIBS and the life jackets are transparent because they were used during the mission. When they were in use, the information of what was behind got printed on paper which gives this ghost effect.